The early history of the UW Geology Museum

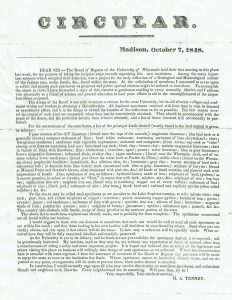

At the very first Board of Regents meeting for the establishment of the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1848, one of the primary topics for discussion was the creation of an exhibit to display of geological and mineralogical samples from around the state. The Board commissioned H. A. Tenney to oversee the solicitation and collection of specimens from the public and the distribution of any duplicate samples to other state educational institutions to encourage public interest in the natural resources of Wisconsin.

At the very first Board of Regents meeting for the establishment of the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1848, one of the primary topics for discussion was the creation of an exhibit to display of geological and mineralogical samples from around the state. The Board commissioned H. A. Tenney to oversee the solicitation and collection of specimens from the public and the distribution of any duplicate samples to other state educational institutions to encourage public interest in the natural resources of Wisconsin.

In 1877, the twenty-eighth year of the University, Science Hall was completed and became the home of all University science departments except astronomy and pharmacy. Most famously, Science Hall was home to the Anatomy department where many cadaver dissections were conducted over the years. In fact, the presence of cadavers and the gothic architecture of the building led to the fabrication of countless spooky tales, some of which were later turned into a novel and a comic series. The Geology Museum got its humble beginnings on the third floor of the original Science Hall building. However, a significant portion of the collections, including the bones of General Sherman’s horse were lost in the devastating fire of 1884.

In 1877, the twenty-eighth year of the University, Science Hall was completed and became the home of all University science departments except astronomy and pharmacy. Most famously, Science Hall was home to the Anatomy department where many cadaver dissections were conducted over the years. In fact, the presence of cadavers and the gothic architecture of the building led to the fabrication of countless spooky tales, some of which were later turned into a novel and a comic series. The Geology Museum got its humble beginnings on the third floor of the original Science Hall building. However, a significant portion of the collections, including the bones of General Sherman’s horse were lost in the devastating fire of 1884.

Plans for the rebuilding of Science Hall got immediately underway and focused on constructing an entirely fireproof building. However, the costs of the rebuild were so staggering that the University was worried it would have to close down. Luckily, the regents were able to secure additional funding from the legislature and the construction got underway. Due to the high costs, the University began the construction without a constructor and soon appointed a Civil Engineering professor, Allen D. Conover, to be the constructing supervisor. Conover was aided by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright, a part time student assistant. The building was completed in December of 1887 despite its many delays, controversies and additional costs.

Plans for the rebuilding of Science Hall got immediately underway and focused on constructing an entirely fireproof building. However, the costs of the rebuild were so staggering that the University was worried it would have to close down. Luckily, the regents were able to secure additional funding from the legislature and the construction got underway. Due to the high costs, the University began the construction without a constructor and soon appointed a Civil Engineering professor, Allen D. Conover, to be the constructing supervisor. Conover was aided by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright, a part time student assistant. The building was completed in December of 1887 despite its many delays, controversies and additional costs.

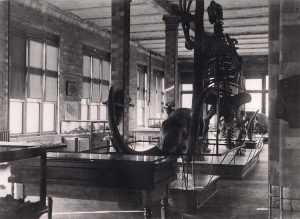

The Geology Museum once again took up residence in Science Hall in 1886. Its collections were tended by R. D. Irving who oversaw the re-founding of the museum in the new building. Due to lack of funds and appropriate staff the museum collections became thin over the years and it remained somewhat neglected until 1929 when the University appointed the first full time curator, Gilbert Rassch. Rassch described the museum collection of 1925 as dwindling and neglected, but around Thanksgiving of 1929 Rassch began the re-organization and modernization of the museum. In 1933, with the depression threatening the existence of the museum, Rassch and geologist Fred Wilhelm devised a novel way to update the museum and increase attendance all on a very tight budget. The two erected miniature models of mastodons, mammoths, and dinosaurs all on plaster plaques that were painted and mounted on the walls of the museum. These plaques can still be seen today in the Vertebrate Room of our museum.

The Geology Museum once again took up residence in Science Hall in 1886. Its collections were tended by R. D. Irving who oversaw the re-founding of the museum in the new building. Due to lack of funds and appropriate staff the museum collections became thin over the years and it remained somewhat neglected until 1929 when the University appointed the first full time curator, Gilbert Rassch. Rassch described the museum collection of 1925 as dwindling and neglected, but around Thanksgiving of 1929 Rassch began the re-organization and modernization of the museum. In 1933, with the depression threatening the existence of the museum, Rassch and geologist Fred Wilhelm devised a novel way to update the museum and increase attendance all on a very tight budget. The two erected miniature models of mastodons, mammoths, and dinosaurs all on plaster plaques that were painted and mounted on the walls of the museum. These plaques can still be seen today in the Vertebrate Room of our museum.

Rassch was the museum curator until 1936 and in that time his efforts greatly enhanced the museum’s collections. In addition to the diorama model construction mentioned above, Rassch saw to the addition of new display cases for existing specimens, the creation of a Driftless Area scene, the construction of a four scene diorama depicting the steps of the formation of Devil’s Lake, and the care of the museum’s largest specimens, including the Boaz Mastodon and the glyptodon replica (which Rassch affectionately referred to as Old Nic and Oswald, respectively).

Rassch was the museum curator until 1936 and in that time his efforts greatly enhanced the museum’s collections. In addition to the diorama model construction mentioned above, Rassch saw to the addition of new display cases for existing specimens, the creation of a Driftless Area scene, the construction of a four scene diorama depicting the steps of the formation of Devil’s Lake, and the care of the museum’s largest specimens, including the Boaz Mastodon and the glyptodon replica (which Rassch affectionately referred to as Old Nic and Oswald, respectively).

A major attraction in the Geology Museum over its entire history has been that of the Boaz mastodon. The bones of the mastodon was discovered by the Dosch children in a family farm streambed after a rainstorm in 1897. The family enjoyed much fame as locals came by their fence to see the amazing giant bones propped up there. By the early 1900s the skeleton had found its way to the Geology Museum, and in 1915 G. M. Schwartz and M. G. Mehl reconstructed it in the museum in Science Hall. About half of the original skeleton was found, while the other half was created by making inverted model of the other side. The skeleton now stands 9.5 feet tall and 15 feet long.